By Dan Golding

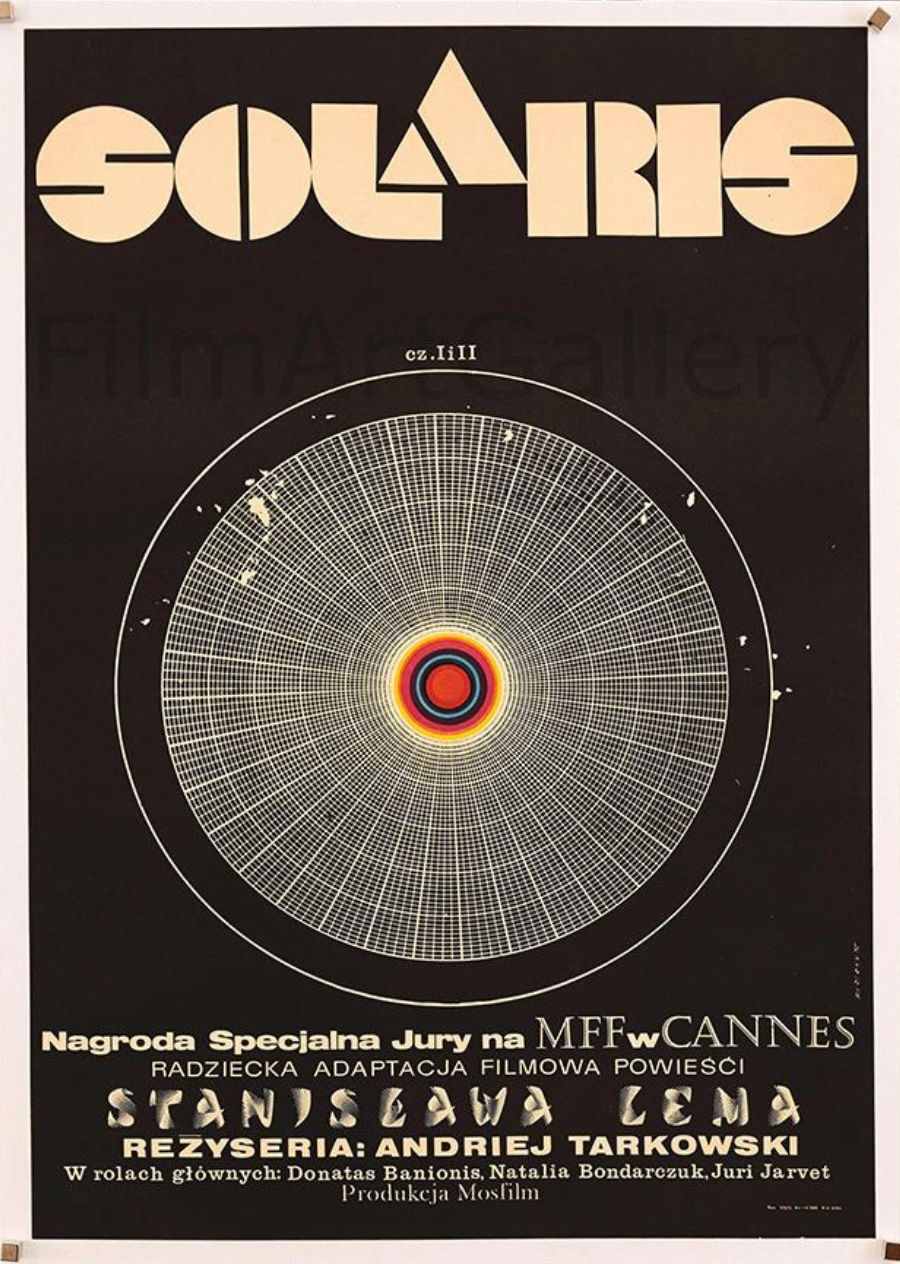

Richard Tognetti can remember the moment exactly. The young Tognetti was watching Solaris, Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1972 Soviet era science fiction epic, with his father. “That was a revelation for me,” Tognetti says. “The film, the music, the space, the images, the beauty of it.” Alongside Tarkovsky’s images, it was his use of JS Bach’s Ich ruf zu dir, Herr Jesu Christ in Solaris that made Tognetti sit up and listen. It was a transformative moment, one that revealed the power of music in cinema.

It’s a fascinating memory because, as with so many of Tarkovsky’s movies, Solaris isn’t notable so much for its musicality as for its long stretches of silence. “Above all, I feel that the sounds of this world are so beautiful in themselves that if only we could learn to listen to them properly, cinema would have no need of music at all,” writes Tarkovsky in his book, Sculpting in Time (1989). To watch Solaris in a movie theatre is to be aware of the film’s spare use of both music and dialogue, as well as the occasional sounds of nature. But primarily, to watch Solaris is to be aware of the rustling of the person in the seat next to you and of the shifting in the seat of your neighbour several rows back.

Far from the bombastic worlds of Hollywood science fiction, Solaris is nothing if not quiet, which is almost certainly what makes Tarkovsky and composer Eduard Artemyev’s use of Bach at a few key moments all the more startling. “This is very judicious use of music, very sparse,” says Tognetti. “But when it happens” – he pauses – “oh, my God. It transcends the visual experience.” After such long stretches of quiet any music at all – let alone something as powerful as Bach – shatters not just Solaris’s silence but our preconceptions about how the soundtrack can work.

Film gives us images for the mind’s eye but it is music that amplifies it into memory. Play a good bit of film music from years ago and chances are that, like Tognetti, you won’t just remember the film, but who you were, where you were and who you were with when you saw it for the first time.

There’s a reason that Tarkovsky – who said that “in my heart of hearts I don’t believe films need music at all” – never followed through and made a movie without it. Music can tell us about a film in ways that its images cannot. As Siegfried Kracauer wrote in his Theory of Film (1960), when silent film faced the addition of music, “ghostly shadows, as volatile as clouds, thus become trustworthy shapes”.

What isn’t as remarked on is what movies give to music. For much of its life so far, the cinema has also been a testing ground for musical creativity, as producers and directors voraciously consumed and repurposed any new sound that might set their pictures apart. What started as commerce for the film industry became artistry for some composers, and the darkened movie theatre served as an unlikely home for new musical technology and new compositional approaches.

If you lived through the 20th century, it is entirely possible that a trip to the movies resulted in hearing the new musical possibilities of electronic instruments, synthesizers and tape experiments. Take Wendy Carlos, for example. In 1968 her pioneering album Switched-On Bach brought the newly invented Moog synthesizer to the world, combining startlingly novel instrumentation with the musically familiar. Just a few years later a cinemagoer would hear Carlos’ music soundtracking A Clockwork Orange (1971), stunning the audience with sound well before the film has even offered up any of its famed ultraviolence. Even from the film’s opening credits, which combines simple shocks of block colour and a terrifying stare from Malcolm McDowell, it is Carlos’ Moog reworkings of Henry Purcell that tells us what kind of an experience we are in for.

Then there’s Delia Derbyshire, who worked at the BBC Radiophonic Workshop and who forged new musical possibilities using tape loops and electronics. Derbyshire was hands-on with the material of this new era of technologically informed music, and within a few months of arriving at the Workshop had transformed Australian composer Ron Grainer’s theme for a then new television series, Doctor Who, into something spectacular. “Did I really write this?” a stunned Grainer asked Derbyshire on hearing the iconic arrangement for the first time. “Most of it,” she replied. Derbyshire’s recording served Doctor Who for its first 17 seasons, and its spectral rattle and hum drove the imagination of television viewers when the BBC’s endearingly cheap sets and costumes might not have otherwise done the trick.

On a soundtrack, exciting and contemporary sounds give their images something more than simple accompaniment. They add vitality. “I like to say you end up hearing with your eyes,” says Tognetti. “It transcends the visual experience.”

The visual experience of film can also be altered by music. What does Vangelis’ wash of synthesizers do for the opening of Blade Runner (1982) and the film’s spectacular images of a future Los Angeles? A city at night might traditionally be soundtracked by a bustling orchestra, suggesting urbanity and life. This kind of sound has almost became a cliché – for Los Angeles alone in movies such as Sunset Boulevard (1950), In a Lonely Place (1950) or, more recently, La La Land (2016). Instead, for Blade Runner Vangelis chose to write music with slow, evolving textures and a melody that lifts and lifts until it falls into an abyss. What we see is a city: what we hear is its scale.

It is not surprising to note that texture and setting are some of the overriding themes of Tognetti’s own soundtracks. “Most of them are water films,” Tognetti laughs. He has written music for films including River (2021) and The Water Diviner (2014). Then there’s Musica Surfica, a documentary which in part follows Tognetti, an enthusiastic surfer himself. But it all began, as Tognetti notes, with a collaboration with Peter Weir, who with films such as Picnic at Hanging Rock, Gallipoli, and Witness made his mark as one of the best directors of music to have emerged from Australia.

“I like to say you end up hearing with your eyes,” says Tognetti. “It transcends the visual experience.”

In 2003, Tognetti wrote music with composers Iva Davies and Christopher Gordon for Weir’s Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World, a naval epic set during the Napoleonic Wars. It’s a remarkable film that has gained a cult-like following in the two decades following its release, in part due to its source material – the Aubrey-Maturin series of novels by Patrick O’Brian – and Weir’s direction, but also because of its impeccable use of music. Russell Crowe and Paul Bettany play mismatched but firm friends at sea who bond over near-death experiences and their own amateur performances of Boccherini and Bach in the captain’s quarters. As with Weir’s previous films, it’s the use of a mix of original score and pre-existing music that steals the show. Ralph Vaughan Williams’s Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis haunts Master and Commander and is particularly memorable in one scene of tragedy at sea.

The use of classical music in film is an echo passed down through directors such as Tarkovsky and Kubrick to Weir, who all have different approaches to music but share an attendant ear for the greats. This can be a formidable tool in a director’s creative arsenal. “The classics, Bach and Beethoven – when these composers are used to great effect by a director, you realise something incredibly powerful is unleashed,” says Tognetti. “It transcends the normal film music experience.

This is a delicate balancing act. “Having worked on films, and worked with composers who’ve worked on films, and worked with directors, you can put any music to a film,” Tognetti continues. “It’s so subjective that it’s verging on the ridiculous.”

Years of internet memes prove this point beyond doubt. Take “The Importance of a Good Soundtrack”, a video uploaded to YouTube by an anonymous user in 2016, which features a familiar scene of Darth Vader inspecting the Imperial troops from 1983’s Return of the Jedi. This time, the scene is cut not to the bombast of John Williams but to the soft and sweetly romantic sounds of ’80s new wave band Spandau Ballet. As Darth Vader walks towards camera, the facial expressions of the terrified Imperial underling read as lustful and tender as Spandau Ballet’s music cultivates this Sith-ful romance.

Images accept a comprehensive array of musical sounds and so good direction and good composition become a question of taste – as well as a matter of not overemphasising the obvious. Entire film genres are sometimes made and broken by music alone. A lonely saxophone might clue us in that we’re watching a film noir long before a femme fatale walks on screen. A single, repeating snare drum pattern from composer Ron Goodwin is all we need to know that Where Eagles Dare (1968) is a war movie, when the only thing that is on screen in the film’s opening sequence is snowy landscape. Take the same images and add a lush French horn and strings, and you could be forgiven for thinking you’re about to watch a nature documentary.

At its finest, film music tells us about more than what we can see. “The worst thing you can do to a scene of unhinged madness,” says Tognetti, “is fill it with crashing and thunderclaps and music.” One of the most remarkable scenes in Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar sees the protagonist astronaut, played by Matthew McConaughey, realise that he has lost 23 years of connection with his children due to a space-travel mix-up. As McConaughey’s character watches archived video messages from home aboard his spaceship and weeps as his family’s lives play out in fast-motion, on the soundtrack composer Hans Zimmer does not reach for an oversized musical emotion, such as sobbing strings or a melodramatic choir. Instead, Zimmer gives us a soft church organ. In a scene where sadness is obvious, Zimmer’s music tells us about loneliness.

Ultimately, Tognetti’s love of Tarkovsky and Solaris’ scarce use of film music has a fascinating corollary in his great director collaborator. “[Peter Weir] told me that he loves music so much that he would like to make a film without music,” says Tognetti. Perversely, perhaps the greatest tribute you could pay to film music would be to leave it out completely and to refract its power through its absence.

That’s the thing about film music – as the meeting point of two artforms, it is greater than the sum of its parts. The soundtrack doesn’t take its power simply from adding one thing to another. Instead, a good soundtrack multiplies and transfigures. Image transforms into emotion and music is transformed into memory.

Years later, you’ll remember the moment exactly.

A Clockwork and Beyond tours to Sydney, Wollongong, Melbourne and Canberra, 12-23 May. Click here to discover the program and book tickets.